One of my biggest issues with the current state of how footy analytics is developing is that it’s oriented toward player production metrics, rather than player value metrics.

What do I mean by this? Well, the development of analytics in the statistical value is geared to much toward understanding the value of a player’s actions on the ball on the field, but not in the wider context of the process toward winning or the wholesome value of a player directly and indirectly. SuperCoach/Champion Data Rankings Points and AFL Player Ratings points, whilst effective if you wanted to ask yourself “how good was this player’s statistical game” don’t answer the inherent question of how that improved that player’s team’s chances of winning. It measures the production, on “ball-involved” or “on-ball” aspect of a player’s performance, but nothing more than that.

For example, for defenders, it’s hard to statistically analyse how they helped their team to win. Intuitively, a keen footy eye will realise that a defender is a good player because of how they adhere to successful structures and as such make opposition ball movement poorer. But it’s difficult to analyse in a statistical sense. For example, if the coaching staff have implemented a successful defensive structure, such as packing the corridor for central throw-ins because the opposition moves the ball through the outside following the throw-in, a player’s value is how apt they are at following that structure and blocking the corridor to force the opposition into a more unusual corridor ball movement. But valuing that analytically or statistically? How do we give a numerical defensive value to the player who does that well? It’s tough. Conceptually, defensively, is all about preventing the opposition from doing what they usually do so you’re measuring the success through the lack of something, rather than the value of actually doing something which is easier to measure. It’s not a concept that’s unique to footy – for example, it exists in all sports like Basketball (long live Grantland).

But today I’m going to look beyond measuring defence where it’s hard to do so analytically, and I’m going to talk about another idiosyncracy of footy as we know it.

Australian football does not have an offside rule. It’s been a feature of the game for over 150 years, as old as the sport itself!

As such, when you’re wholly talking about footy analytics, I don’t think that you can categorise it into what some sports analysts have dubbed “territory-invasion” sports such as Rugby and Soccer, this being one example. “Territory” is a more distinct concept in those sports, because of the nature of an offside line and the protection of territory behind the offside line. Not saying it doesn’t exist in Australian football – your defensive 50 is certainly “your” territory, but the concept of “invading” territory behind ball or player was smashed not long after the game was invented over 150 years ago… by Tom Wills, the father of Australian football. How he did it is explained very well in Time and Space by James Coventry, so if you haven’t already, picked up a copy and read it yourself.

If you’ve read my stuff, I go off a tangent often… but it’s all linked back to what I’ll write from here on it. Because the lessons we’ve learned in analytically analysing defenders we can also apply to other positions, most pertinently key forwards and their value … and it’s not something that we can learn from other sports, because players ahead of the ball given no existence of an offside line impacts the quality of ball movement, and that gives values to key forwards, as these key forwards typically play in front of the ball and impact ball movement.

If defensive roles have value because a defender’s action and inaction changes the production of the opposition players for the worse, such as worse decision making in ball movement because of good defensive positioning, that’s something we can also apply to forwards conceptually – even if it’s something that we can’t really statistically measure. Key Forwards have value because they play in such a way that adds value because how make their teammates produce better actions, and their oppositions worse actions. Okay, I’ve minced my words a bit so read that again if you have to!

If we compare salaries to analysing “production”, we all understand it for defence. Nobody is suggesting that Alex Rance is overpaid, despite the fact he’s being paid somewhere in the vicinity of $600k a year, ie one of the highest paid players in the league, even though there’s an analytics disconnect between the intuitive (and correct) value of his salary. I mean, he was rated roughly outside the league’s top 60 players according to AFL Player Ratings Points at the time he signed that deal, but we were able to “explain away” the disconnect between that and the contract he signed (and he could have fetched more from other clubs like Brisbane) because of the fact we all understand the difficulty in measuring defence analytically.

So what other position also have disconnected between what their value is measured by their salaries, and their analytical performance? Key forwards, because the play ahead of the ball and impact other players on the field. Cloke’s last contract was a lot at the Pies, Freo were throwing around millions at any key forward they could approach over the last two years, and obviously Tom Boyd signed a multi-million deal as a teenager. There’s clearly a disconnect with how much they get paid, and conventional, analytical ways of measuring their on-ball production, as no key forward is in the top 16 of AFL Player Ratings Point. But why is there a disconnect? Because of the same reasons – their value isn’t so much their on-ball production that can be measured statistically, but how they change the actions of their teammates for the better, and their opposition for the worse.

A lot of the top draft picks and massive percentages of the salary cap goes to key forwards. Sydney are literally paying around one-fifth of their salary cap for two players – Tippett and Franklin – and there’s a disconnect between how much they’re getting paid and their “analytics of direct production” given that Franklin is “only” the 17th ranked player currently in AFL Player Ratings Points and Tippett all the way down in 80th. For defenders it’s easy to “explain away” this difference – we understand it conceptually, even if we find it difficult to measure it differently. But for forwards – well, we need another left-field thought process to get there.

In case you’re wondering, yes, it’s thoughts like this that tick in my head when I can’t get to sleep! Basically, conceptually, how can we “explain away” the difference in analytical production measurement and the (correct) intuitive value of these key forwards that is explained by player salaries?

My initial thoughts are this: key forwards do two things that give them inherent value. Firstly, they help their team’s quality of ball movement (ergo not so much through their own direct actions, but rather how they impact on other players on the field much like a defender would. Except in this case it’s the teammates and not the opposition, and for the better and not for the worse). The second thing they do is that they play a pseudo-defensive role in their opposition’s attack from defence.

How exactly do key forwards help their team’s ball movement? Well, we have to think about a key forward vs a resting midfielder or a small forward or whatever the alternative to not having a key forward is. Basically, picture a typical ball movement scenario – whether it be bursting from a stoppage, switching the play, quick ball movement through the corridor or whatever – but basically, picture those scenarios to be identical, but ahead of the ball (which they can be because there’s no such thing as an offside), the player is different, a tall player vs a small forward. Does the quality of the ball movement change because of the difference in player ahead of the ball?

My answer is yes. Firstly, most obviously, a smaller player is likely to be intercepted against than a key forward (“halving a contest” using the technical term). But it goes a bit deeper than that. I think the quality of ball movement is improved because a key forward is less likely to lead to the flanks or pockets than a smaller player because they can create their own space (pushing smaller players out of the way etc.) rather than having to find space near the flanks, and the central position of the ball movement is a better shot location than a pocket – for example, a goal is more likely to be kicked if the spill from the contest is directly in front of goal 30m out, rather than in the pocket 30m out.

But it’s not just that. The presence of a big man up the ground helps ball movement through decision making. Teams are more likely to simply move the ball closer to goal because they have the confidence that they have a big unit up there who might mark the ball.

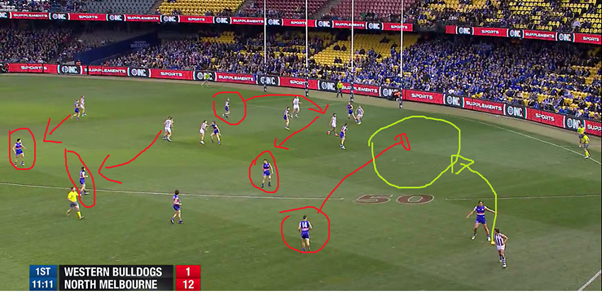

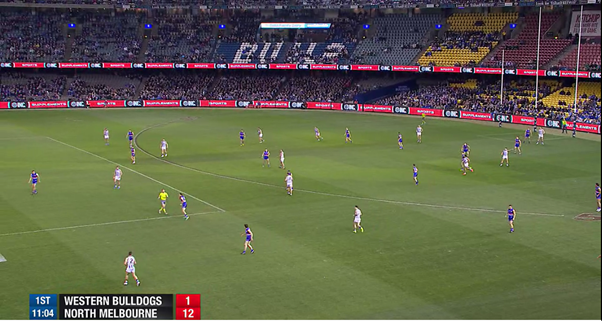

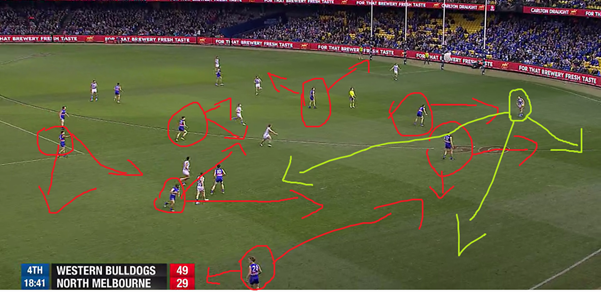

Take the Western Bulldogs‘ loss in Round 6 this year to North Melbourne. The Dogs lost Tom Boyd to injury the game before, and didn’t have a key forward in the team, with only a second ruck in Roughead or Campbell resting forward that match and the rest of the forward line being small or medium players (I still get nightmares of us kicking it to skinny Bailey Dale as a marking target … the nightmares are less scary with a premiership cup however!) The quality of the Dogs‘ ball movement was poor, because they chose not to kick toward goal because of the lack of tall timber up forward. Lachie Hunter, who played on the half back flank, won 44 touches because of the fact the Dogs over-used the ball sideways and backwards because of the lack of structure forward of the ball impacted their decision making and confidence in moving the ball in a direct-to-goal way. The Dogs ball movement, which can be measured in the sense that they kicked just six goals for the match, was poor.

I’m hoping with player tracking data from next year, that’s the next step. The Bulldogs have mooted a hackathon next year with this type of data, and if I had the computer-whiz skills to code this, the first thing I’d try and measure is the “player-gravity” nature on how some players impact the quality of ball movement ahead (or behind) of the ball. All things being equal, do key forwards really get the ball to gravitate toward them in better ball movement locations, and if so, which key forwards are better at doing that than others? I’ve always said that I find it a bit strange that somebody as big as Tom Hawkins leads to the flanks, rather than crashes packs in a more central location, which is obviously a better place for the ball to be inside 50 – but can we prove it analytically that Hawkins is a poor “gravity” player using player tracking and ball data?

The other reason I think key forwards have value intuitively, as measured by their salaries, that can’t be measured directly by ball-involved analytics, is that they play a pseudo-defensive role on the oppositions defence. What do I mean by that? Well basically, the opposition change their way they attack from the defence given the mere presence of a player in the forward line. Simply put, if you’re a big unit, you’re not going to be left alone that often, because you don’t want a player zoning off then a different player who zones on being not key defender sized and being outmarked. Simply because of the size of that player, it’s more destructive if a big guy gets zoned off than if a smaller player gets zoned off. And that, even indirectly, impacts the quality of how an opposition attacks from its defence. The inflexibility that the opposition has in defending a bigger player impacts in attack therefore logically it is a sort of pseudo-defensive value of a key position forward.

Picture this. Imagine Tom Lynch in the goalsquare against, say, Heath Grundy. You’d say that Grundy is a good chance of defending Lynch, but Jake Lloyd playing as a running defender isn’t. But if Tom Lynch was replaced by a smaller player, say Aaron Hall as a small forward, you could play Lloyd on the smaller player, have him run off that small player with the knowledge that Grundy can zone off and pick up Hall if worst comes to worst, and it’s not the end of the world and in fact means that he’s likely to intercept against Hall. But Lynch? He impacts how Sydney would like to attack and position their defenders for optimal attack out of defence.

That’s what I love about the unique nature of the Australian game – it, as a result, gives unique concepts to think about in an analytical sense. Trying to understand the value of key forwards is just one of them.